This is the third in a series of posts about true events behind my historical novel The Shifting Winds. Here we look at the American side of the fur trade led by the venerable mountain men. These rugged men led the American effort at about the time Dr. John McLoughlin was sent to take charge of the Columbia District for his employer, the honorable British Hudson’s Bay Company. The Astor venture, having failed for the Americans, left the United States without much footing in the Columbia, but fur trade prospects had already begun brewing for the Americans in another arena, the Rocky Mountains on the edge of their now undisputed Louisiana Territory.

Before I focus on that American trade directed by St. Louis companies, I want to present a painting and go back to that young man I mentioned in post number 2, John Colter, a member of the historic Lewis and Clark expedition.

The American Scheme

The painting below by modern-day artist Andy Thomas of Carthage, Missouri, represents John Colter. Thomas calls the image “The First Mountain Man.” This artist offers many paintings of historic people and events, and his mountain man appealed to me.

I was looking online for photos to represent my characters when I came across it.

I wanted to put together a poster and banner with images portraying my protagonist, American pioneer Jennie Haviland, and the two men in Oregon who were vying for her affections, British Hudson’s Bay Company clerk Alan Radford, and American mountain man Jake Johnston.

Alan was a well-dressed gentleman of the times and I had no trouble finding an 1800s fashion plate that had the right look for him.

I found one complete with frock coat and tall beaver hat, even if the face wasn’t quite as gorgeous as I imagined him. And I found a young woman in a fashion plate with period dress, her face hidden by a bonnet so folks can imagine her appearance as they choose.

But there were no fashion plates for mountain men. Most of the mountain man pictures I found were of crusty old fellows with long, scraggly beards. Now, there may have been some mountaineers like them, but trapping in the Rockies was not a business for old men. These guys had to be tough and in their prime, and most were clean shaven.

Part of the reason for shaving was that the Native American men they associated with had little face hair and plucked what grew, so the women seeing a bearded white man might laugh disparagingly and call him a dog face. If these trappers wanted to win the hearts of these women, shaving was a good idea–not to mention the greater ease of keeping small critters out of their soup.

Anyway, I came across this image of a mountain man and it spoke to me. The guy in the painting had the gravitas I was looking for, and with the artist’s permission, John Colter now plays the role of Jake for me on my marketing materials for the book.

He doesn’t look exactly the way I see Jake either, but he has keen eyes that might be about to twinkle and a bit of don’t-mess-with-me attitude I can’t help but like. He’ll probably shave when he gets back to camp.

And that brings us to the real John Colter. He was born in Virginia sometime around 1775, his father evidently having come from Ireland. The family moved to the Kentucky frontier around 1780 when John was a young boy. At about 30 years of age he impressed Meriwether Lewis with his frontier skills, and Lewis recruited him for the Lewis and Clark Expedition as a private.

Colter may have been a little hotheaded because he got into a fracas with his sergeant even before they left and threatened to shoot the man, but somehow it got smoothed over and he became a valued member of the team and one of the best hunters. Lewis learned he could trust Colter to handle many difficult situations. The man showed skill in bartering with the tribes they met, and he would strike out alone wherever Lewis or Clark asked him to go and always find his way.

Two months before the end of the journey home, the expedition met some trappers headed west, and Colter joined them as a worthy addition, given his fresh knowledge of much of the territory. He went out alone for them during the winter, traveling some 500 miles through the wilderness to establish trade with the Crow nation, and was probably the first white man to see such sights as the spewing Yellowstone wonders, which came to be known as Colter’s Hell. Many stories of his skills and scrapes have been the stuff of books and movies, but probably none so dramatic as his run from the Blackfeet.

Colter was canoeing up the Jefferson River with another trapper, Potts, when several hundred Blackfeet showed up and demanded the two go ashore. The Blackfeet killed Potts in the incident, hacking him to death, then stripped Colter naked and told him to run. He soon realized they expected him to run for his life. His nose began to bleed, but he kept going as blood streamed and was well ahead of all but one of his pursuers.

With a suddenness that startled the man on his tail, Colter came to an abrupt stop and swung around to face him, arms wide. Caught by surprise at Colter’s actions, and perhaps the blood streaming over Colter’s naked body, the man also tried to stop but fell forward as he threw a spear and plunged it into the ground. Colter snatched up the broken weapon and killed him, then grabbed a blanket from him and fled the others. After a five-mile run he reached the Madison River and jumped in, taking refuge in a beaver lodge until nightfall when he escaped.

Thus he became something of a legend. When he did return to civilization a few years later he visited William Clark of the Lewis and Clark expedition and reported on his travels, adding considerable detail for Clark’s maps. He got married and farmed in Missouri awhile before fighting in the War of 1812. He never returned to the mountains.

About ten years after the war, just before Dr. John McLoughlin went out to the Columbia, some men of St. Louis, William Ashley and Andrew Henry, put together a fur company that significantly impacted the American fur trade. Prior to that time, most furs were acquired through trade with the Indians. But Ashley and Henry led their own trappers into the west, where they built a couple of forts and wintered with the Crow tribe. In the spring of 1824 the trappers went into the Green River country and found it rich in beaver. Ashley came up with a working scheme when he put together the first supply train and took the caravan to the Rockies the next summer so the trappers didn’t have to haul their furs to market in St. Louis. The annual rendezvous had begun.

The above painting by Alfred Jacob Miller shows the supply caravan bringing supplies to the Rocky Mountains for the annual rendezvous of the mountain men. Miller went out with the supply train in 1837 and created many portraits of the landscapes and mountaineers and Native Americans he saw there. The man on the white horse is the Scottish adventurer William Drummond Stewart who hired Miller to take the journey with him to record the event.

The Rocky Mountain Rendezvous lasted from 1825 until 1840 when beaver began to play out and prices dropped because men discovered silk hats to replace their beavers. It was a great run and the rendezvous an uproarious party when men let loose after they’d spent a year working hard in dangerous conditions. The supply trains brought out pure alcohol to mix with the clear water of the mountain streams, adding to the craziness. Friendly tribes gathered with the mountaineers, and many of the Americans took wives from these tribes or enjoyed temporary liaisons.

This Miller portrait shows the rip roaring greeting trappers typically gave to the arriving caravan. Again the Scot Stewart is on the white horse.

During these years the Americans pretty well kept to the Rockies, while the British reaped the Oregon Territory of beaver there. Sometimes they bumped up against each other, and competition was fierce. The British ultimately pursued a scorched earth policy to make sure there weren’t enough beaver left on the west side to lure the Americans to Oregon.

Because of the supply train system many of the American trappers never went back home, and after years of living in the wilderness, often with wives and children they knew wouldn’t be accepted in the States, they felt adrift when the mountain life ended. So after the last rendezvous of 1840 quite a few went to Oregon anyway and decided to become settlers, a situation that didn’t always set well with the British. Thus legendary mountain man Joe Meek, a major player in my book, enters the stage, along with others who are named in the pages, accompanied by the fictional Jake Johnston. This was just two years before the book’s 1842 opening.

Dr. McLoughlin, another major historic player in my book, found himself caught in a dilemma between honoring the interests of his nation and following his own humanitarian instincts.

But when the good doctor first went to the Oregon Country in 1824 the British had a near monopoly there and prospects all looked rosy.

Gowans, Fred R. Rocky Mountain Rendezvous: A History of the Fur Trade Rendezvous 1825-1840. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1976.

Various websites.

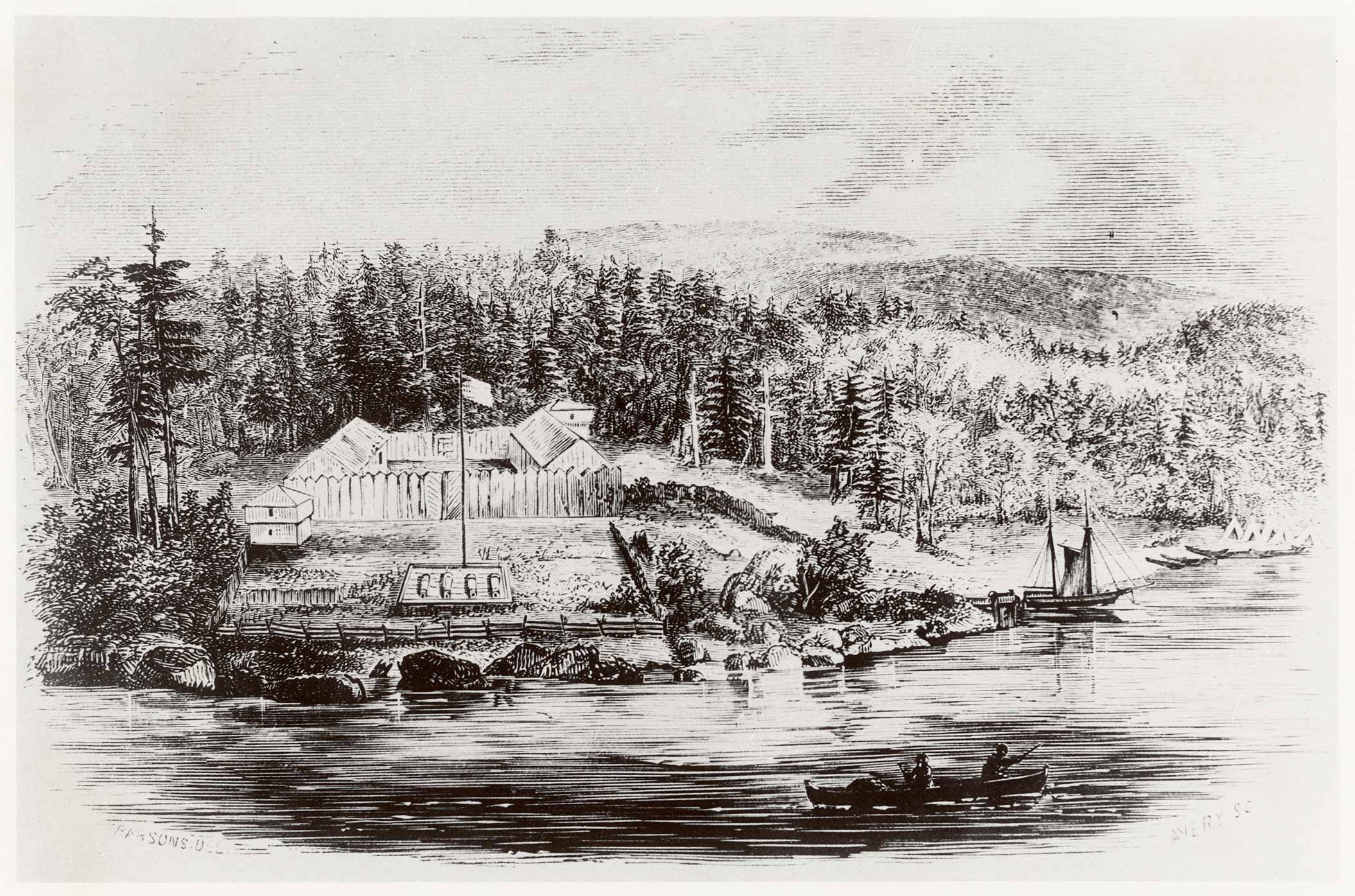

Next: British Stronghold