Where the story comes to life . . .

The photo above brings stone and sea together, the upper line of the stone echoing that notch where the sea gleams bright blue when the air is right. This is one of the pillars in the Bohonagh circle near Rosscarbery, Ireland, sacred circle of the protagonist’s clan in my story.

With this last post in my “Going There 2024” series I’d like to reflect on the highlights of my recent trip to immerse myself in the main settings of my upcoming historical novel. More than anywhere I went it was Rosscarbery on the southern coast of Ireland where my story lived. I had time to wander by myself there and let it all soak in.

I passed a few people when I went down to the beach below but for the most part it was a solitary stroll. There I learned about beach grass on that Irish coast–unlike Oregon’s tall beach grass that found its way into my Irish story and has to be replaced with the low grasses I noticed here.

This is why I “go there.” It’s part of my work as an author. To see the places, and feel them, and try to get it right, so I can bring the reader into these worlds with me when they read the words of my books.

My explorations showed me the lay of the land along the bayshore, which will help with my descriptions. The stunning beauty of an afternoon sunlight on the water might come into a scene.

And the circle? There wasn’t another soul where I climbed to the circle and stepped inside to experience it and imagine how it must have been when musicians played and people danced. Or when they came alone to pray, stepping inside through the portal stones, honoring their Great Ancestress, Grand Mother of them all.

The next most critical site where I could feel my story come alive was at Newgrange. The lofty passage tomb with its own partial circle of stones. The incredible passageway where the light of the winter solstice sunrise shines all the way down to the inner chamber with its meticulous corbelled roof, filling the chamber with light.

I learned that the tomb did not lie in front of the ridge as I had described it, but actually crowned the ridge, the back side having sloughed down the hill behind so it covered some of the surrounding kerbstones and standing stones. The archaeologist who restored the monument brought it back as near as possible to what it was when my characters walked down the long, narrow passage into the vault, and I of course thought of them when I walked inside myself.

Back in Dublin I marveled at the goldwork produced during the time of my protagonist, a young woman goldsmith, as I walked through the remarkable array of gold displayed in the National Museum of Ireland – Archaeology. Here’s just one example of a collection there from about 800 to 700 B.C.

On another excursion I saw more clearly the rugged stones of the great rock, the outcrop of the Rock of Cashel that stands bold upon a broad green plain. I could better describe it now after climbing up those knobby limestone walls myself–not the walls built by men on top of the rock but those left by nature long before, the only walls my characters would have seen.

And when I left Ireland for Hallstatt I would see and learn more. Why Hallstatt when my story is about ancient Ireland? Because of the Celts. Yes, when we think of the Celts we may well think of Ireland. But at the time of my story there wouldn’t have been any Celts in Ireland yet. Not in any numbers anyway. Their homeland in 750 B.C. would have been in Hallstatt, Austria. So to bring the Celts into my story we go there. And I followed.

I had visited this remarkable place once before. But with this visit I would refresh my mind’s image of the brilliant water of that lake between steeper slopes and more massive cliffs than I remembered. I thrilled to the play of light on the water. Was it something different in the skies this time? Or the brush of wind that came with unsettled weather? Or was it always so and I forgot?

It took me awhile to find the waterfall I describe in my story. But there it was above the museum, fog hiding the higher slopes.

I reached the falls at last and will show it more clearly now in the description. Back down on the lake’s edge, I got a better sense of the sheer drops on those bold mountains where my characters walk.

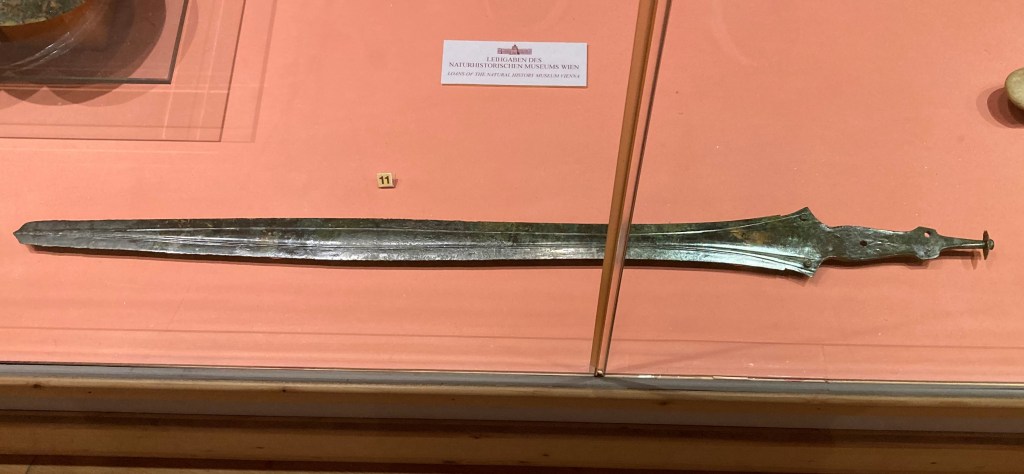

In the Hallstatt Museum I saw a Hallstatt sword, like those I describe in my story. Here’s the real thing, which had been found just up those mountains. I could almost hear the swish of bronze slicing the air.

So much. I left these amazing places, my head full of images, words. How to describe? How to take the images from my head and put them into the words that will let the reader see and feel. Ah! The challenge, the joy, for every writer.

Out of the many experiences I had on my trip this spring of 2024, these are the ones that stand out to me, highlights that will surely affect the work. The journey gave me so much. People along the way offered so much. I am ever grateful.

As I continue to absorb the wonder, may these memories reflect in the pages. Story came to life here.

NOTE: This concludes the “2024 Going There” series. I’ll keep the list of titles on the sidebar so you can navigate the stories whenever you might like. I’ve had fun reliving the moments and hope you’ve enjoyed sharing some of them with me. I’ll continue to post snapshots from the trip on social media now and then. I love hearing your thoughts. Thanks so much.