A lovely crowd turned out for my book reading and signing at Annie Bloom’s Books in Portland. It was such a cold, rainy evening. Icy rain hammered me as I drove into the city. I wondered if anyone would come out on such a night. But Portlanders don’t let anything like a little rain stop them. The people came.

Here is Annie’s as I arrived early on that wet evening. But a warm welcome awaited inside.

Here is Annie’s as I arrived early on that wet evening. But a warm welcome awaited inside.

Molly Bloom, the silky black cat who rules the store, soon made her presence known, and I was determined to get her picture this time. I never got my own picture of her last time I had an event there with my first book, A Place of Her Own. So I must confess the rest of my pictures of the event are of Molly. None of the crowd. None of me speaking. Just Molly.

She seemed a little shy at first. “I’m not quite ready to go out there yet.” I knew the feeling. Here she has tucked herself under the table where I sat to do my reading, a little different from other venues where I usually stand. But it was pleasant, conversational.

She seemed a little shy at first. “I’m not quite ready to go out there yet.” I knew the feeling. Here she has tucked herself under the table where I sat to do my reading, a little different from other venues where I usually stand. But it was pleasant, conversational.

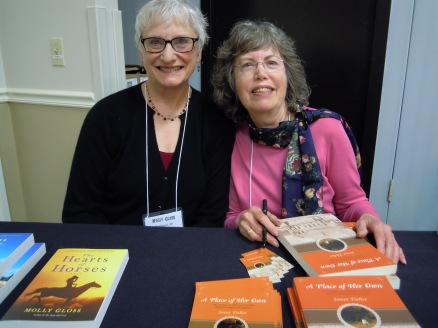

I do want to thank my cousin-in-law Judy Fisher, who helped with serving wine after my presentation. She and my cousin Jack came over from Lake Oswego, and it was great to see them. And a special thanks to Stephanie, the human at Annie’s who handled the event and introduced me.

I had some surprises. A friend who had known my father came. She had worked with him when he served on the State Board of Education years ago, and even had dinner once at my parents’ house at the farm. Also in attendance was someone who had worked on the archeological digs at Champoeg, a significant locale in the story of The Shifting Winds.

Molly kept busy before we started. “I just need to check something over here in the stacks.”

Molly kept busy before we started. “I just need to check something over here in the stacks.”

As I began to do my reading Molly started working the crowd in earnest. She traipsed around the chairs. She paused for gentle strokes on her silky fur. She leaped into laps. My camera was on the corner of my table. I considered stopping midsentence to get a better picture, but decided that would break the flow, and it was an intense scene. I could have asked someone beforehand to do pictures, but didn’t. Even with Molly’s antics the reading was well received.

And we had a great Q & A. Many of the people knew the history that surrounds my story, so we had a vibrant interaction. Quite a few were interested in A Place of Her Own too. All in all, a delightful event. And afterward Molly was all worn out.

Sigh. “It’s a big job running an event like this. But I am content. It went well.”

Sigh. “It’s a big job running an event like this. But I am content. It went well.”

My thanks to everyone at Annie’s. This was my go-to bookstore when I lived in Portland, just up the street, and I always love going back there. It’s such a pleasure to be able to share my own work in this warm and friendly place. Like Molly, I was content.

NEXT UP: News on an exciting upcoming event.