As my upcoming July 16 book event at Fort Vancouver nears, this new blog series sets the stage for that historic place and the part it plays in my book The Shifting Winds.

The overview of the true history of the world’s shifting winds continues in this post as the unknown Pacific Northwest keeps luring explorers into the region. Of course, mere curiosity would not compel them like the hopes of gaining a new possession and the riches the land offered. While the glitter of gold may have drawn earlier navigators like the Spanish and Portuguese to the centers of their discoveries, another prize put a gleam in men’s eyes and prompted a race to win the Pacific Northwest territory.

The prime fur was beaver like these pelts at right displayed in the reconstructed Fort Vancouver warehouse. Without the fur, Fort Vancouver would not have been. This was the chief bounty, thanks to the beaver hat which became a popular fashion statement in Europe and the States, as traders from two nations pressed for advantage in one land.

The Race for Possession

Thomas Jefferson had been interested in the Pacific Northwest for some time when he took office as President of the United States in 1801, but without a contiguous territory overland he was not ready to consider more than an independent state in the region. Even that he considered to be a hazardous endeavor for the young nation.

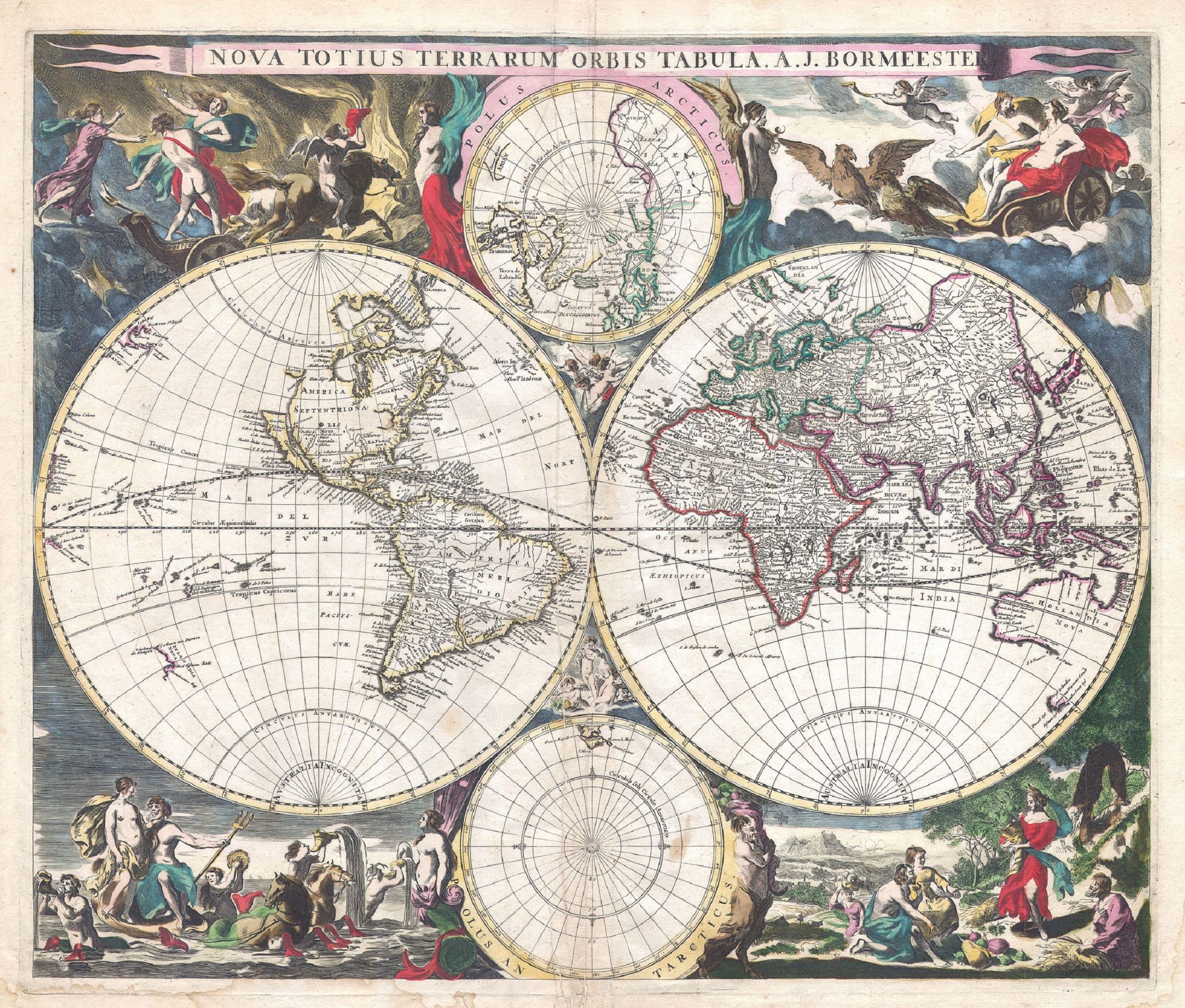

This 1794 double hemisphere wall map of the world, or terraqueouis globe, by Samuel Dunn shows the new discoveries and marginal delineations. From Geographicus.

This 1794 double hemisphere wall map of the world, or terraqueouis globe, by Samuel Dunn shows the new discoveries and marginal delineations. From Geographicus.

So the maps they are a-changing. It’s beginning to look more familiar.

Jefferson was intrigued by the 1765 report of Major Robert Rogers, who had written of a great “River of the West, or Ouragon River” said to flow west into the Pacific Ocean, a potential northwest passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific. And by 1792 the US navigator Captain Robert Gray had already discovered and named the Columbia River. Soon afterward British Lieutenant William Broughton, under the command of Captain George Vancouver, had sailed some 120 miles upriver.

But the condition of the Columbia beyond that point remained an unknown to these explorers. Was it the River of the West? The Ouragon? Or the Oregon? And would it allow direct transportation—or at least an easy portage—to a navigable river flowing east to the Atlantic, essentially the sought after northwest passage?

Zooming in on Dunn’s above map you can see two Rivers of the West flowing into the Pacific. Perhaps folks were still trying to decide, or hedging their bets.

Zooming in on Dunn’s above map you can see two Rivers of the West flowing into the Pacific. Perhaps folks were still trying to decide, or hedging their bets.

Meanwhile Canadian fur traders had begun to consider the overland route to the Pacific. Alexander Mackenzie, a partner in the Canadian North West Company, became a firm skeptic of the northwest passage after following a large river into the northern interior in hopes of locating the mythical route, only to find that this river emptied into the Arctic. Convinced that no northwest passage for sea vessels existed, he insisted if Canadians wanted to reach the Pacific from Hudson’s Bay they should go overland.

Mackenzie organized an expedition to do just that, intending to cross the Rockies, then go down the River of the West. His party came across a major waterway, which he assumed to be this elusive stream, but he discovered it was not the river dubbed Columbia by the American Captain Gray, but a more northerly river which would be named the Fraser. Mackenzie’s party reached the coast at Port Meares in July 1793 after a harrowing journey, the first transcontinental crossing north of Mexico.

Jefferson must have been pondering all this when the international winds shifted again, and Napoleon’s dilemma became Jefferson’s boon. The United States had been negotiating with France for New Orleans, because the Americans wanted the mouth of the Mississippi. But when the entirety of the Louisiana Territory, once a French possession, was dropped back into Napoleon’s lap through various treaties, he knew he was no longer in a position to protect it, and he greatly feared that his arch enemy, the British, now ensconced in Canada, would ultimately take it from him.

Jefferson was just as fearful at the prospect of the powerful French on his border, but he didn’t want to make this longtime friend an adversary. He was surprised when Napoleon offered to sell the Louisiana Territory to the United States for a song, and suddenly the fledgling US nation nearly doubled its size.

The Great Explorers – Lewis & Clark: Halftone reproduction of drawing by Frederic Remington in Collier’s Magazine, 1906 May 12, from Library of Congress.

The Great Explorers – Lewis & Clark: Halftone reproduction of drawing by Frederic Remington in Collier’s Magazine, 1906 May 12, from Library of Congress.

The Americans didn’t know much about the Louisiana Territory, not even the boundaries on the north and south, though its western boundary lay somewhere along the crest of the Rockies. Louisiana now provided that contiguous link with the territory of the west. So Jefferson sent out Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to see what the United States had bought and to explore and map the region. However, he didn’t want them to stop at the western edge of the newly acquired Louisiana, but to continue into the west to explore that land of uncertain possession, including the intriguing river their compatriot Gray had discovered.

Leaving St. Louis in the spring of 1804, Lewis and Clark proceeded up the Missouri River, crossed the Rocky Mountains and came down the Clearwater River to the Snake before making their way into the Columbia River, which they navigated all the way out to Young’s Bay. The Columbia proved to be a magnificent waterway, but not a northwest passage, given the ruggedness of the land between it and the east flowing streams. A young member of the expedition named John Colter would later gain fame for adventures upon his return into the mountains to look for furs, leading many to call him the first mountain man. More about him in the next post.

When Lewis and Clark returned to the States in 1806, Americans became excited about commercial possibilities in the west. Fur dealer John Jacob Astor approached the North West Company about joining forces, but when they refused, he founded his own Pacific Fur Company. He sent out two parties to the Columbia, one by land, led by Wilson Price Hunt, and one by sea aboard the Tonquin.

Men from the Tonquin arrived in the Columbia in March 1811 and set up a trading post on the south bank, naming it Fort Astoria. The overland party straggled in almost a year later after a grueling trek.

The above 1813 sketch of Fort Astoria was created by Gabriel Franchère, one of Astor’s men from the Tonquin, and later published in 1819 with Franchère’s account of the venture.

The above 1813 sketch of Fort Astoria was created by Gabriel Franchère, one of Astor’s men from the Tonquin, and later published in 1819 with Franchère’s account of the venture.

At about the same time, the Canadian North West Company sent David Thompson over the mountains to establish fur trading posts and continue to the mouth of the Columbia. The Astorians offered Thompson a friendly greeting, but the War of 1812 erupted, putting the men on opposite sides of the conflict. Through a complicated series of events, the fort of Astoria was sold under some duress and turned over to the Canadians. A British warship, the HMS Raccoon, entered the Columbia soon afterward, its captain hoping to capture the fort, but the sale had already occurred.

Author Robert C. Johnson, in his book John McLoughlin, describes the disappointment of the warship’s Captain William Black when he saw Fort Astoria. “‘What! Is this the fort I have heard so much of?’ exclaimed Black. ‘Good God, I could batter it down with a four-pounder in two hours.'” He took possession and renamed it Fort George after the British king.

When this news reached Astor in New York he was not pleased, but the deed was done. Given the remoteness of the fort, its sale and surrender were unknown to negotiators of the Treaty of Ghent ending the war in 1814. The treaty provided that territory and possessions taken by one nation from the other should be restored. Because of this agreement, the British were expected to restore Fort George to the Americans. However, a question remained as to whether the fort was taken or sold. That and other controversies between the nations led to another treaty in 1818 to settle the boundary issues in the region.

Spain and Russia also came into the question, but the United States was haggling with Spain over Florida and didn’t want to press too hard on the southern boundary with Spain, though the line was established the next year at the 42nd parallel. Russia was pushing for a boundary in the north where they would take all territory down to the 51st, but neither Britain or the United States would accept that and finally negotiated it back to 54-40. With Spain and Russia settled, that left the Americans and the British.

The US claim to the territory was founded on Gray’s discovery of the Columbia, the Lewis and Clark expedition, the founding and restoring of Astoria, and the title acquired from Spain. After settling with the Spanish, the United States contended that any rights Spain possessed as a result of discovery had passed to the United States. The British claim was based on early voyages along the northwest coast, land exploration by Mackenzie, North West Company posts on the Columbia and Fraser Rivers, and Broughton’s ascent up the Columbia River.

The 1818 treaty set the boundary between Britain and the United States at the 49th parallel from the Lake of the Woods to the Stony Mountains, the Rockies, each nation ceding some land to make a straight border, but at the Rockies they hit a snag. Americans suggested continuing the 49th parallel to the coast, though many of their countrymen wanted to push the British north all the way to 54-40. Britain wanted the boundary to drop southward and follow the Columbia River so they could retain the lucrative fur trade there. With the two sides unable to agree, the treaty declared that the Oregon territory be jointly occupied between the United States and Britain for 10 years, giving them time to settle on a boundary between them. The treaty allowed both nations the right of settlement and trade, but neither could claim title to the land. Agreement would take much longer than 10 years.

While the Americans and British hassled over the details of negotiation, another virtual war raged between the Montreal-based North West Company and the other major British fur company doing business in the region, the London-based Hudson’s Bay Company, resulting in the deaths of many trappers and traders. To end hostilities the beleaguered companies finally merged in 1821 under the Hudson’s Bay Company.

The history of the restoration of Fort George (Astoria) to the United States seems a little murky. As the 1818 treaty was concluding, a representative of the US government arrived at the fort to receive the fort’s surrender, and the US flag was raised. By some accounts, as soon as the US representative sailed away, the US flag came down. In any case, the Canadian North West Company continued to maintain the post, perhaps for lack of further US action, and when that company ceased to exist, the British Hudson’s Bay Company took it over, more or less by default.

Dr. John McLoughlin, formerly an employee of the North West Company, became a Hudson’s Bay Company man and was assigned in 1824 as commander of the HBC western district. He would soon make a grand entry at Fort George.

Carey, Charles H., LLD. General History of Oregon: Through Early Statehood. Portland, OR: Binfords & Mort, 1971.

Johnson, Robert C. John McLoughlin: “Father of Oregon.” Portland, OR: Binfords & Mort, 1958.

Various websites.

Next: Mountain Men