I first visited Fort Vancouver some years ago to research a short segment for one of my early attempts at an Oregon Trail novel, and the place put me right back in time. I was so inspired by the authentic reproduction of this historic fort I knew I had to write another book with more scenes set there. That became The Shifting Winds, which I’m honored to be presenting at the fort this Saturday, July 16, at 2 pm.

In this post I want to talk about how this wonderful reconstruction came to be.

Archaeology and Record Keepers

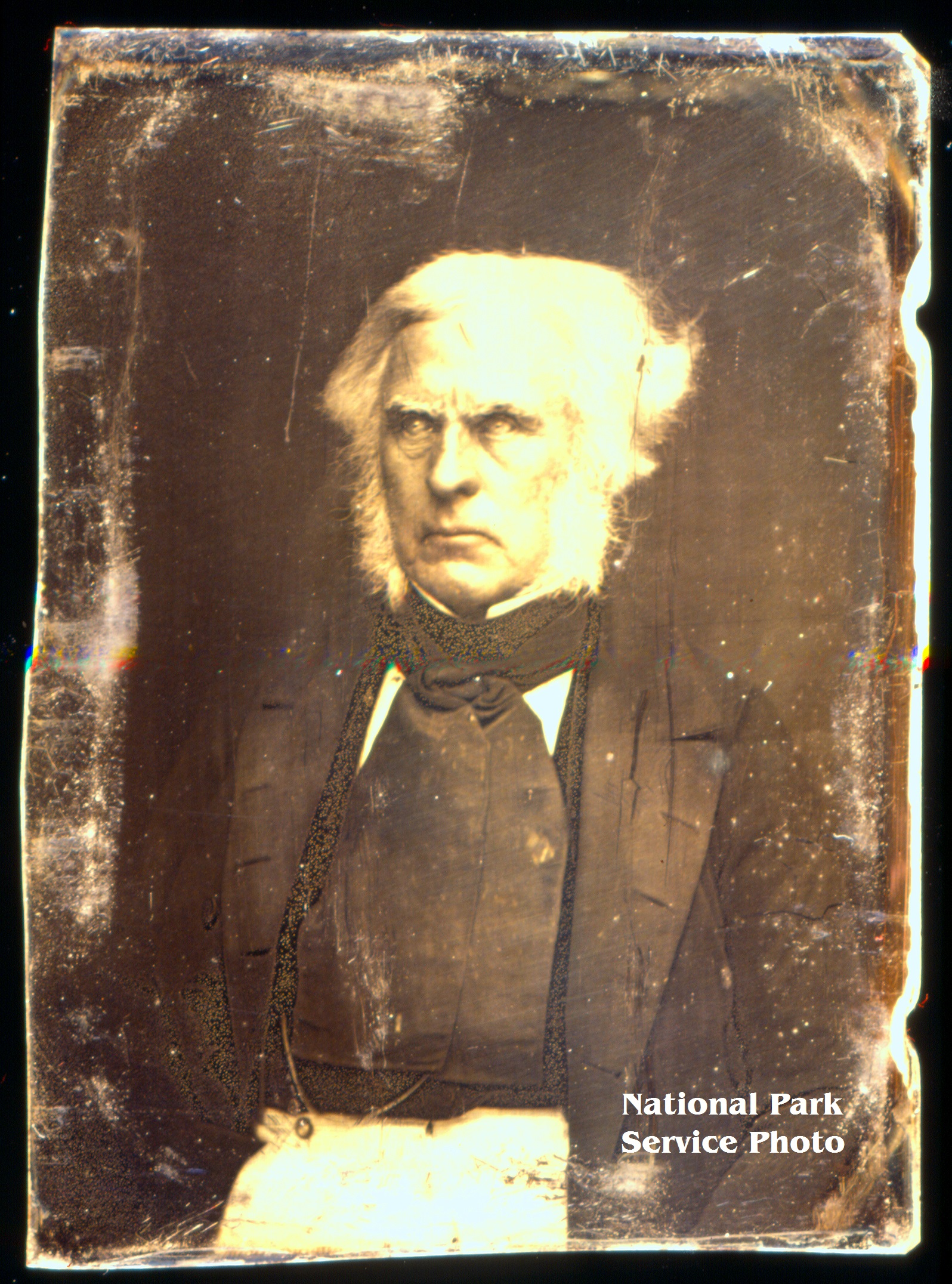

The British Hudson’s Bay Company chose a location on the north bank of the Columbia River for their western headquarters in the Oregon Country because they felt optimistic about Britain holding land on that side of the river once London and Washington agreed on a boundary between the two nations. But in 1824 when Dr. John McLoughlin and his boss Governor George Simpson selected the site, enough uncertainty hung over the region that they didn’t want to make a huge investment.

Also unsure of the friendliness of the local tribes, they erected the first palisade walls about a mile inland, creating a simple fur trading post on a bluff about a mile from the river with bastions on at least two corners, ready to defend themselves against attack.

Several events came together to change their perspective. First, the joint occupancy treaty of 1818 between the British and the United States was extended indefinitely in 1827. The Native Americans proved to be agreeable traders, and the distance from the river proved to be a bloody nuisance.

So in 1828 they pulled up stakes, literally, and moved the whole thing a mile closer to the river to the spot where the reconstructed fort lies today.

Christened in 1829, the new fort would serve the Company for many years. But it didn’t remain static. It kept changing over time like a living, breathing organism that sloughs off old skin while growing new. The fort walls kept moving. The fort doubled in size by 1836. Apparently the officers found their space too small.

They would expand again, moving the south wall farther out—and the east wall—again.

Buildings changed. The first Big House in the original west half began to sag until someone described its condition as so dilapidated it was ready to fall down around them. They rebuilt a new Big House in the east half where you can see it reconstructed today.

So why the reconstruction? Why did the original disappear? And why the constant change?

In short, wood rots—especially in a place where rain soaks the land for more than half the year. And little critters move in to feed on wood fiber.

Constant maintenance was required, and sometimes they just tore down buildings and constructed new. They continually replaced rotting pickets in the stockade and repaired leaky roofs. When the British finally lost the land on which the fort stood—as you must know they did—the Hudson’s Bay Company was allowed to stay on for a while, but they soon began moving the bulk of their business to Fort Victoria. London and Washington had finally agreed on a border in 1846, drawing the line along the 49th parallel, well north of Fort Vancouver, although giving the British Victoria along with the entirety of Vancouver Island.

By 1860 the Company abandoned the fort and the United States Army assumed control. But they found most of the buildings unsuitable for their purposes and in dilapidated condition. In a few years rot and fire destroyed what was left.

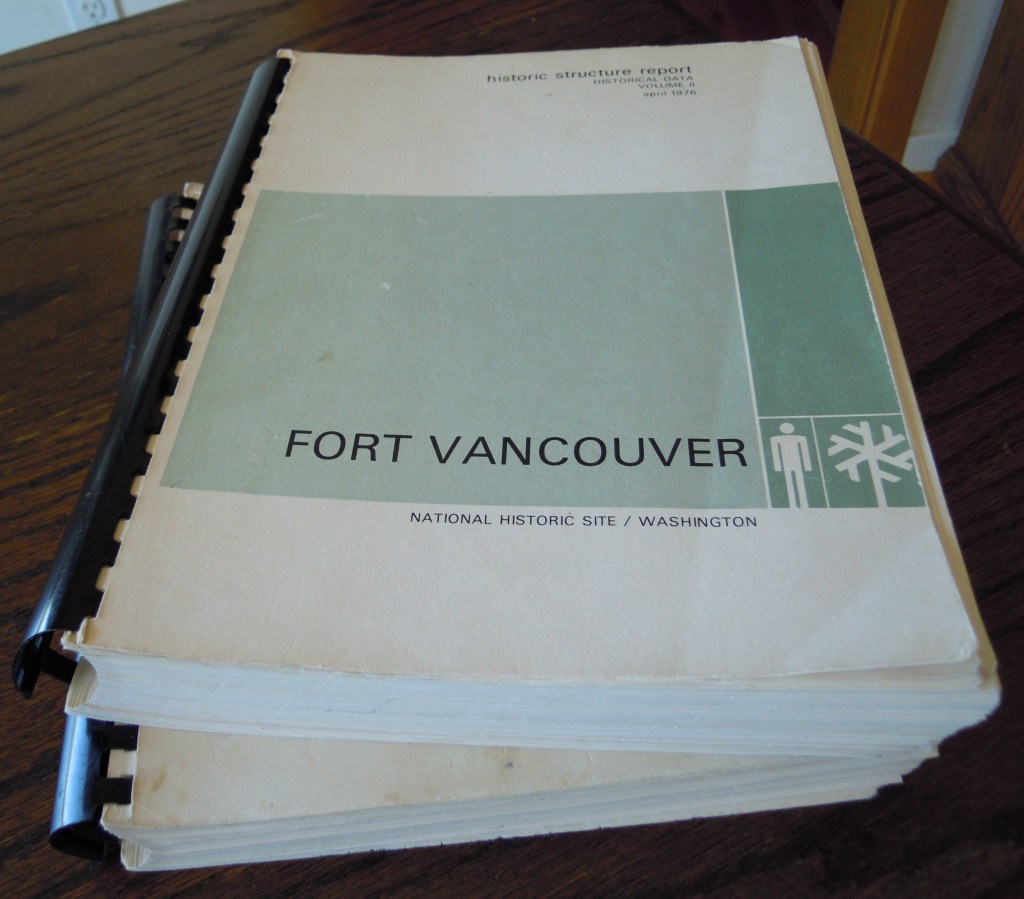

Yet some historians didn’t forget. In the 1940s the National Park Service began exploring the possibility of reconstruction. If they were going to do it they wanted to do it right. On my first visit to the reconstructed fort in the 1980s a curator there loaned me these two large volumes of a “Historic Structures Report” by John A. Hussey and the historic preservation team.

The volumes described the detailed research that went into this re-creation, a wealth of information. When I called about returning the volumes, the curator told me that if I continued to find them useful I should keep them because they had plenty of copies. What a boon to my research!

Now of course the report is online, offering a glimpse of the magnitude of the project. But I have spent many hours poring over the printed books.

As early as 1947 National Park Service archeologists dug into the soil to find footings of buildings and remains of those moving walls at their various locations. They found tools, pottery, even Spode china on the site of the Big House–something in blue on white, perhaps to match these on display in the Big House dining hall, or Mess Hall, like the one shown here. Meanwhile, researchers looked into records. The Hudson’s Bay Company, still a functioning business in the UK, generously opened their remarkable archives for this study.

The British had kept detailed records.

Researchers were also given access to similar HBC posts, now in Canada, and those were studied and photographed for comparison. The Company tended to follow similar plans from one fort to another, so those helped in decisions about the finer points.

Books written in the day offered observations of the fort. Libraries across the United States and Canada held useful tidbits. Many fort visitors wrote about their impressions, sometimes drawing detailed sketches and maps. These were often dated and helped show the constant rearrangements going on over the fort’s life. Researchers scrutinized maps, drawings, every descriptive statement they could find. Much of that went into this report, along with bits of story that add flavor.

The above lithograph was based on a water color by Henry J. Warre painted during his 1845 visit. My thanks to Meagan Huff, assistant curator at the fort, for sending me this copy from the National Park Service collection. She pointed out a change the artists in London made to Warre’s original.

Did Warre depict shepherds? Or voyageurs? Perhaps wanting the image more colorful the London artists replaced the original figures in the foreground with Native Americans, but in Plains tribe dress, not realizing that these tribes did not frequent the area.

Because the fort changed so much from year to year, the preservation team needed to pick a date, and they decided to reconstruct to the year 1845. That’s close to the date of my novel, which has scenes at the fort in 1842 and 1843. So as I read the report I had to make careful distinctions between the 1845 fort I saw and the 1842 fort I would describe

For instance, in one scene Dr. McLoughlin and my fictional clerk Alan walk across the grounds from the Big House to the Indian Trade Store in the western courtyard. Today you’ll find that store on the east side, almost straight across from the Big House, a short walk. But in 1842 that store was over in the western side where the Fur Store stands today. A longer stroll.

Perhaps the most conspicuous difference would be the bastion you can see in Warre’s 1845 image above. There was no bastion in 1842, so you won’t find reference to a bastion in the book. But I have shown it in blog and Facebook posts because it looks so fort-like. Fort Vancouver was more trading post and supply depot than fortress. Caution required walls but not big guns.

The bastion went up in 1844, not because of danger, but because of protocol.

Hussey relays the story in the report. A ship sailed up the Columbia in 1844 and offered a 7-gun salute. But the fort couldn’t answer the salute because they had no cannons mounted for action.

Although they’d put up bastions on the old fort, they hadn’t bothered with a bastion in the new fort, things being so peaceful. But not to be able to answer a salute—well, that just wouldn’t do. So they built one.

Given the troublesome nature of some of the pesky Americans coming into the country it seemed a good idea anyway.

Another change was the New Office, built in 1845 to replace the Old Office. The Old Office was one of the oldest buildings of the fort, the first thing constructed, given its function so vital to the fort’s purpose. That Old Office still served the fort in 1845, because the new one offered temporary living quarters for a ship captain who stayed on for a while, adding excitement for the gentlemen with his many parties in the new structure. This New Office, or “Counting House” as it was sometimes called, has been reconstructed. The Old Office has not, although perhaps one day it will be. It stood close by its replacement at least until 1847 when the good captain departed. The old building with its dark exterior shows clearly in a water color sketch drawn in 1846 or 1847.

The fort required considerable bookkeeping. Clerks like my fictional Alan Radford generally entered service through apprenticeship, nearly all of them from Britain. Because of the many applicants, family connections helped. These clerks were usually well educated and knew some accounting beforehand. The Company wanted reliable, loyal clerks working in the office, men who would be discreet and keep Company business confidential. These accounting clerks held one of the better paid jobs for gentlemen at the fort.

I took particular interest in the office, given that Alan is a major player in my book. Other buildings of special interest to me were the Big House where Jennie stays during her visit for the Christmas Ball and where the ball takes place, and the Bachelor’s Quarters where American mountain man Jake Johnston stays, having joined the party for his own reasons. Accountants like Alan lived in the office, but most clerks lived in the Bachelor’s Quarters, a long building divided into multiple rooms or apartments. And when gentlemen came to visit, the clerks often got bumped to accommodate the visitors.

However, Alan appeared none too pleased when McLoughlin allowed Jake a room in the Bachelor’s Quarters. When Jennie asked Jake what was wrong with Alan, Jake grinned.

“Well,” he said, “it’s only gentlemen who are allowed to stay inside the fort, and I don’t think Radford considers me a gentleman.”

She wasn’t sure Jake was a gentleman either, but she was surprised at the rigidity.

The Bachelor’s Quarters have not been reconstructed yet either, but the report offers excellent detail.

Fisher, Janet. The Shifting Winds. Guilford, CT, Helena, MT: TwoDot, Globe Pequot Press, Rowman & Littlefield, 2016.

Hussey, John A. Historical Structures Report Historical Data, Vol. I and II. Denver Service Center, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1972, 1976.

Next: Making the Past Live